This handsome new monograph on the most important German Romantic painter was originally commissioned by a French publishing house and was written with a non-German audience in mind. With the opening at the National Gallery, London of Spirit of an age: 19th-century paintings from the Nationalgalerie, Berlin (7 March-13 May), it will undoubtedy help to enhance familiarity with this area of art, so thinly represented in British collections and so often overlooked art-lovers.

The author, himself German and a distinguished scholar in the field, is at pains to situate Friedrich in the widest possible context. The book, he declares at the outset, “represents a first attempt to break open the homogeneous outlines of European Romanticism, strip its content of any national characteristics, and relate that content to individuals".

He is particularly adept at identifying points of contact between French and German Romantic sensibilities. Chateaubriand’s “eye of the soul” is tellingly contrasted with Friedrich’s formulation of “the spiritual eye”, and David d’Angers' early and discerning appreciation of the German painter is noted. Deeply suspicious of analysis by reference to ethnic traits, Dr Hofmann is also conscious that, in the 20th century, the Nazi’s invention of a “manly”, Germanic Friedrich for a time perverted the just appreciation of the artist on the international scene.

This does not mean that Dr Hofmann is not, at the same time, a sensitive and knowledgeable guide to the specific North German social and cultural milieu in which Friedrich flourished. He shows how various strains of subjectivity and religiosity, and a strong Protestant sense of self-reliance, endemic to the intellectual world of Kant, Lessing and Herder, informed the artist and his work.

German political aspirations, especially in the wake of the Napoleonic occupation and its aftermath, are assessed for their impact on Friedrich. (The presence in his paintings of figures in Old German costume is always a clue to patriotic intentions.) Dr Hofmann’s comments on Friedrich’s tense, fluctuating relationship with Goethe provide an amusing window onto the contradictions of German artistic life in the early 19th century. Goethe, so certain in his aesthetic convictions, set the theme for an 1805 art contest; the brash young artist ignored it, producing works of which the Grand Old Man could not approve; nonetheless he shared first prize.

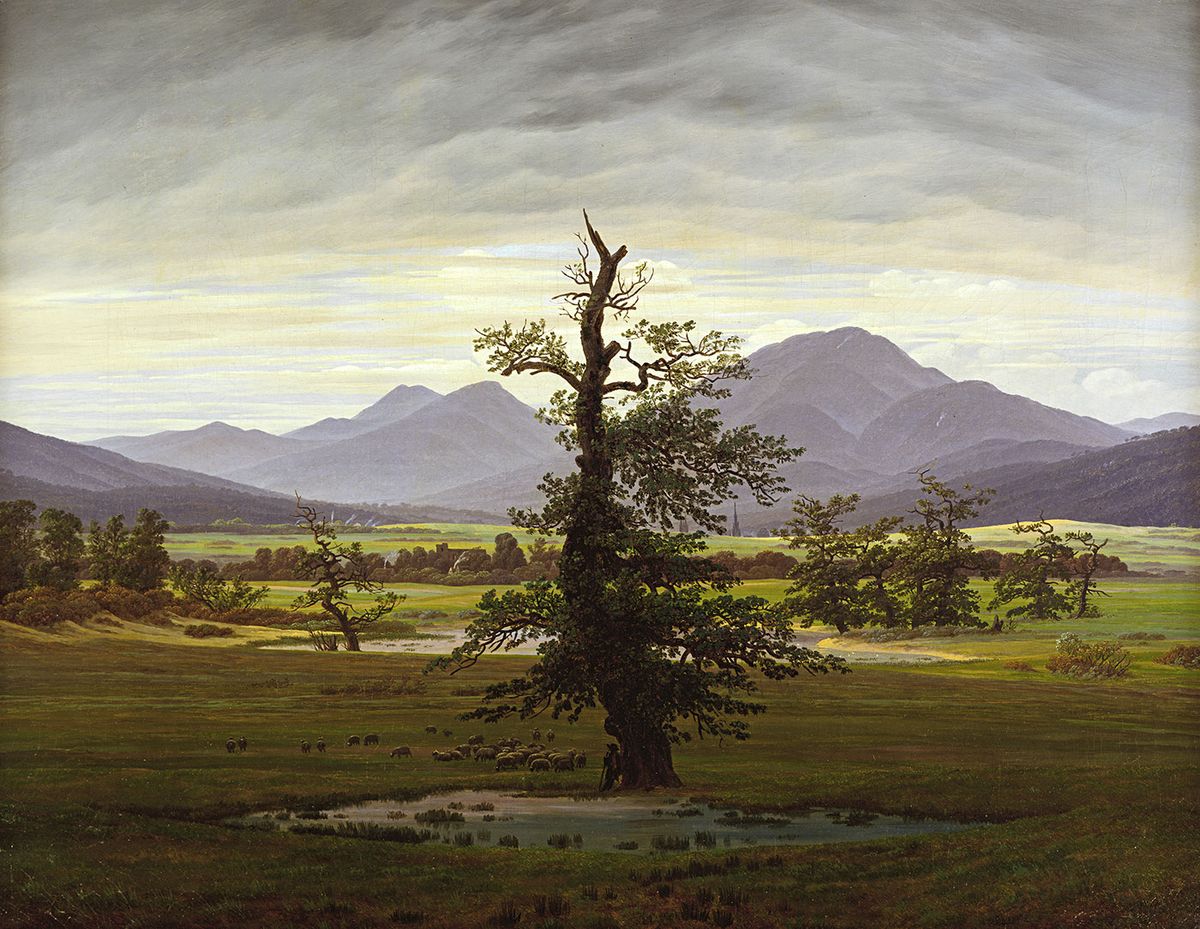

After an introductory chapter establishing the principal themes of his study, Dr Hofmann analyses three key early works, the Tetschen Altar and the pendants Monk by the sea and Abbey in the oak wood. It is here, in his analyses of individual works and clear elucidation of the revolutionary implications of Friedrich’s innovations, where Dr Hofmann is at his most compelling. He shows how the artist arrived early, and almost intuitively, at the formal strategies he would stick with throughout his career. These included the rejection of traditional staffage, perspective and recession in favour of a headlong dive into deep space and the abrupt adjoining of near and distant nature. “Without the mediation of perspective,” Dr Hofmann writes, “nearness is transformed ultimately into inaccessible distance.” Moreover, where the human figure enters into such boundless space, its relation to nature can only be enigmatic and invite interpretation.

In a wide-ranging chapter entitled “The obscure total idea”, Dr Hofmann analyses Friedrich’s repeated use of the concealed triptych format. As the artist came to understand, this subtle tripartite division of the composition, reminiscent of an altarpiece, could not fail to instill even domestic scenes with implications of the sacred. He also traces the steps Friedrich followed from the imitation of nature—and he was a keen observer and recorder of natural phenomena—to the generalisation of the motif by means of a rhythmic structuring of the composition. This allowed the artist to invest his works with poetic feelings and, ultimately, transcendent significance. Dr Hofmann calls it the “iconisation of landscape”.

This analysis is followed by an intriguing discussion of the artist's private life and the role in played in his art, particularly after his marriage in 1818. The pleasures of shared domesticity and the home inspired some of Friedrich’s most haunting works where man and woman together confront the unknown.

When it comes to his own often original interpretations of individual works, Dr Hofmann is scrupulous in indicating where and how they differ from those of other German scholars, notably Helmut Börsch-Supan, the doyen of Friedrich studies. His urgent, engaged tone correctly suggests that a lively debate is on-going. He is perhaps less attentive to English-language contributions to the field, listing Joseph Leo Koerner’s 1990 Mitchell Prize-winning monograph in the bibliography but nowhere referring to Koerner’s ideas in the text. He notes in passing of the Winter landscape in Dortmund that “an almost identical version came to the National Gallery in London [in 1987], where it is claimed to be the original.” However, he never addresses the strong evidence that John Leighton brought to bear in 1990 in putting forth that claim.

The book ends with a series of appendices that include some of Friedrich's writings and, helpfully, Friedrich von Ramdohr’s scathing 1809 critique of the Tetschen Altarpiece and the artist’s spirited self-defence. These are key documents and it is worthwhile to have them in an easily-accessible English translation. The translation of the volume as a whole, by Mary Whittall, is adept and fluent throughout.

An attractive and more than usually thoughtful introduction to Friedrich, Dr Hofmann’s monograph is also a rich lode of ideas and perceptions on this compelling painter which students of 19th-century German art will mine to their profit.

- Werner Hofmann, Caspar David Friedrich (Thames & Hudson,London, 2000), 300 pp, 43 b/w ills, 150 col. ills, £39.95 (hb).